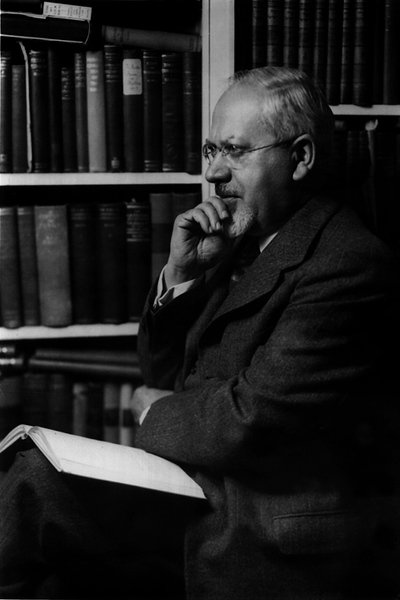

Mordecai Menahem Kaplan (June 11, 1881 – November 8, 1983) American rabbi and founder of Reconstructionism was born in Sventzian, Lithuania, the son of Rabbi Israel Kaplan and Chaya Nehama Kaplan. His father was a prominent Talmudic scholar who had received rabbinic ordination in Lithuania from the most outstanding rabbis of the day. The family emigrated to New York City when Mordecai was eight years old. Kaplan attended City College of New York (B.A. 1900), as well as Columbia University (M. A. 1905) and received rabbinical ordination from the Jewish Theological Seminary (1902).

The traditional education which he received mostly from his father, gave Kaplan a solid grounding in classical rabbinic texts. Because he had both a traditional and a secular education, spoke English without an accent, and thereby was able to relate to young people well, he was engaged as a minister [the title of rabbi came later] by the “modern” New York Orthodox congregation Kehilath Jeshurun in 1903.

Although the congregation was happy with his work, the young rabbi was tortured with doubts as his graduate studies began to undermine his traditional beliefs. During his last year at Kehilath Jeshurun (1908) he met and married Lena Rubin, daughter of a well-known family in the congregation. When in 1909 he was invited by Solomon Schechter, the head of the Jewish Theological Seminary, to become principal of its newly created Teachers’ Institute, Kaplan enthusiastically accepted the position. On his honeymoon to Europe he also met with Rabbi Isaac Jacob Reines from whom he received rabbinic ordination.

Kaplan remained at the Jewish Theological Seminary, the center of the Conservative movement, training rabbis and teachers until he retired in 1963. As the first director of the Teachers’ Institute, he laid the foundations for Jewish education in America. Working closely with Samson Benderly, the Director of the Board of Jewish Education in New York City, he helped train all of the educational leaders of the next generation.

Kaplan was a strong personality and a demanding teacher. For many years he taught homiletics and midrash (classical rabbinic homilies) to rabbinical students at the Seminary in addition to “Philosophies of Judaism.” Critical of his colleagues who seemed to be only concerned with scholarly issues, Kaplan dealt with the central religious questions that troubled his students. His own graduate studies where he had concentrated on sociology led him to formulate a religious ideology that emphasized the link between religion and experience. Because experience changes, religion changes, and thus Kaplan believed it important to find ways in which beliefs and rituals could function in the modern era as they did in the past. To do this might mean changing a ritual, dropping it completely, or substituting something new. Heavily influenced by the utilitarians and by William James, Kaplan called himself a functionalist. He was ready to pursue the path most likely to make religion and particularly Judaism functional in the American setting.

Although the perfection of the individual might be the aim of religion, Kaplan believed that this goal could only be achieved within the context of a community. He held that Jews must have more in common than their religion for Judaism to survive in the secular culture of the modern era. Throughout the ages Judaism as the evolving religious civilization of the Jewish people bound them together into a vital organic entity. A vigorous Jewish life in America could be brought into being he maintained only with the creation of new institutions appropriate to a democratic technologically advanced society. Kaplan had the vision of the expanded synagogue as the vehicle for the survival of Jewish Civilization. In 1917, the Jewish Center on 86th Street in Manhattan, a magnificent building with many recreational facilities in addition to a synagogue, was dedicated with Kaplan serving as rabbi. It quickly became the prototype for many other synagogues-centers in the United States and Canada.

Kaplan’s thinking became increasingly radical leading to his departure from the Jewish Center in 1922 with a large group of supporters to organize the Society for the Advancement of Judaism (SAJ), also in New York City. He attempted to establish his ideology, which he called Reconstructionism, as a school of thought within the Jewish community rather than as a separate denomination in order not to contribute to the fragmentation of American Jewry. Reconstructionism defined Judaism as an evolving religious civilization and stressed Judaism’s quest for social justice as well as individual salvation or fulfillment as the primary values of Jewish life.

In 1934 Kaplan published his magnum opus, Judaism as a Civilization, which became the landmark for second generation American Jewish leaders desperately seeking a way to live both as Jews and as Americans. He held that one could live in two civilizations (the Jewish and the American) without any sense of tension or contradiction because the two cultures were absolutely compatible. His major thrust was to set the Jewish people, their past experience and their present welfare at the center of his conception of Judaism. The Torah (Hebrew Scriptures) revelation and God were all explained in terms relating to Jewish peoplehood. Because he did not see Judaism as a system of dogmas or a set of laws, he helped even the most skeptical of modern Jews to relate to Jewish civilization.

In the years following the publication of his magnum opus in 1934, Kaplan produced a series of works that spelled out his philosophy. Of particular importance are The Meaning of God in Modern Jewish Religion (1937), his primary theological work, and The Future of the American Jew (1948) where he concentrated on the application of his philosophy.

Kaplan used his position as rabbi at the SAJ to explore new rituals, reformulate liturgies and experiment with new prayers. In 1922, he inaugurated the first Bat Mitzvah when his daughter Judith turned 12½. The New Haggadah (for the Passover seder service) which he published in 1941 and The Sabbath Prayerbook which appeared in 1945 shocked and outraged many traditional Jews. In 1945 following the publication of his prayerbook, he was excommunicated (a herem or ban was issued) by the Union of Orthodox Rabbis of the United States and Canada and according to the New York Times, his prayerbook was publicly burned during the herem ceremony held at the Hotel McAlpin in New York City.

Kaplan was a lifelong Zionist believing that Jewish civilization required the natural setting of its own land in order to flourish and grow. Active in Zionist affairs, he represented the Zionist Organization of America at the opening exercises of the Hebrew University in 1925. He was a good friend of Chaim Weizmann who visited him whenever the Zionist leader was in New York. Deeply influenced by the cultural Zionist Ahad Ha-Am, Kaplan later stated that this Zionist thinker revealed to him “the spiritual reality of the Jewish people.”

Kaplan’s Zionism and his devotion to the Jewish people existed alongside a very profound commitment to American culture and its ideals. Not only were the values of American Jewish Civilization mutually supportive but Jewish culture (or any subculture) must be the vehicle for transmitting democratic values. His metaphor for American ethnic life was not the melting-pot where differences disappeared but, like his colleague Horace Kallen, the orchestra where the various voices blended together in perfect harmony. In addition, Kaplan believed that the Jewish community in America must be pluralistic i.e. hospitable to all forms of Jewish commitment and that there must be a place for democracy even within the synagogue where Jews choose under the guidance of their rabbi the ways to express their values and beliefs. According to Kaplan, when it comes to Jewish life in a modern democratic society, tradition and the Jewish law have a “vote but not a veto” over group policies and individual behavior.