Round 11

In 2022 we will be celebrating the centennial not only of the SAJ’s founding, but also of Judith Kaplan Eisenstein’s Bat Mitzvah. With that in mind, we ask: What famous 20th-century rabbi wrote the following regarding Bat Mitzvah?

“Clear logic and principles of pedagogy virtually require equal celebration for a girl when she reaches the age of responsibility for mitzvot. … The difference which is made in the celebration for a boy and a girl upon reaching maturity makes a very hurtful impression on the feelings of the maturing girl, who has in all other areas attained equality.”

Question: Was it:

(a) Ira Eisenstein;

(b) Mordecai Kaplan;

(c) Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg;

(d) Stephen Wise;

(e) Moshe Feinstein; or

(f) Robert Gordis?

Answer: (c) Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg

The writer was Rabbi Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg (1884-1966), a fascinating figure in the history of modern Orthodoxy. Rabbi Weinberg is often known by the title of his most famous work, the Seridei Aish, and, indeed, the quoted passage is from a responsum published in that collection. (Unfortunately, the responsum is undated, and the collection was not completely published until 1966, the year of Rabbi Weinberg’s death.)

The prize goes to Ittai Hershman. Honorable mention to Richard Blum, Shel Schiffman, and Jonathan Zimet, all of whom got the correct answer but were just a little slower in submitting it.

Full disclosure: Rabbi Weinberg was writing about celebrating a girl’s becoming a Bat Mitzvah (and, at that, outside of the synagogue), not about any ritual recognition of the transition from Jewish childhood to adulthood. Still, his view was notably liberal, in its time, within Orthodoxy. For the highly interested, the full text of the responsum (in Hebrew) is available here.

Round 10

In a letter to the chairman of the board of trustees of a well-known synagogue, a prominent American rabbi wrote the following in defense of another prominent American rabbi, whose authority was then under attack:

“In Jewish tradition, the office of its Rabbi, who is authorized to speak for the entire Jewish people, young and old, rich and poor, is highly sacrosanct. To take it upon oneself to render a legal decision in the matter of law in the presence of the Rabbi is to incur divine punishment (Erubin 63a). While we do not subscribe to the severity of the punishment, we have to reckon with the principle that for Jewish life to survive, authorized rabbinic leadership must be respected. … No self-respecting Rabbi can afford to have the laity exercise authority in matters pertaining to the synagogue ritual or the pulpit.”

Question: Was it:

(a) Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan writing about Rabbi Alan Miller (1971)?

(b) Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan writing about Rabbi Ira Eisenstein (1956)?

(c) Rabbi Milton Steinberg writing about Rabbi Ira Eisenstein (1944)?

(d) Rabbi David de Sola Pool writing about Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan (1921)?

Answer: (a) Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan writing about Rabbi Alan Miller (1971)

The letter in question* was dated May 18, 1971 and was written by Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan to Robert L. Krause, then the chairman of the board of trustees of the Society for the Advancement of Judaism (SAJ), concerning Rabbi Alan Miller. Interestingly, almost everyone who participated in this round of the quiz went for the trap we set with “Rabbi David de Sola Pool writing about Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan in 1921,” when Kaplan was still the rabbi of The Jewish Center, which certainly seemed plausible, if not (as some respondents claimed) “obvious”.

The prize goes to George Hyman, who, although he tried to hedge a bit, did get the correct answer.

Almost as interesting as Kaplan’s letter to Krause is the memorandum, dated June 16, 1971, that Rabbi Ira Eisenstein wrote to Rabbi Kaplan in response to the letter. Among other criticisms contained in that memorandum, Rabbi Eisenstein complained that Rabbi Kaplan “quote[d] the Talmud to the effect that one must not ‘take upon one’s self the responsibility of rendering a legal decision in the matter of law in the presence of the Rabbi [sic] .’ It seems to me that for many years you have tried to make the point that when it comes to ritual we must not invoke the halakhah.”

In addition, Rabbi Eisenstein wrote that, “When we prepared the Guide to Jewish Ritual at one of the conventions of the Federation of Reconstructionist Congregations, we did so jointly with the lay people. We did this precisely because we believed that in matters of ritual the laity should have an equal voice since religious service is intended for their inspiration and edification, and rabbinical authority should be looked upon as the authority of expertness rather than power. In fact this is exactly what you and I did when it came to the question of giving aliyot to women [at the SAJ]. We did not make the final decision at all. We initiated the idea; we recommended it; we strongly defended the concept but until a consensus was achieved at a membership meeting no action was taken. This meant, in effect, that the laity has a veto power over the rabbi rather than vice versa.”

*containing the following statements: “In Jewish tradition, the office of its Rabbi, who is authorized to speak for the entire Jewish people, young and old, rich and poor, is highly sacrosanct. To take it upon oneself to render a legal decision in the matter of law in the presence of the Rabbi is to incur divine punishment (Erubin 63a). While we do not subscribe to the severity of the punishment, we have to reckon with the principle that for Jewish life to survive, authorized rabbinic leadership must be respected. … No self-respecting Rabbi can afford to have the laity exercise authority in matters pertaining to the synagogue ritual or the pulpit.”

Round 9

We occasionally hear a grumble to the effect that the Kaplan Quiz is too “heavy”. Want a little popular culture in the quiz? Try this:

One of Rabbi Kaplan’s sons-in-law was a prominent entertainment lawyer and producer.

Question: Which two of the following four celebrities were his clients?

(a) Doris Day

(b) Paul Newman

(c) Ethel Merman

(d) Zero Mostel

Answer: (a) Doris Day and (d) Zero Mostel

The trick here was not to take the Ethel Merman bait, which almost everyone went for. The correct answer is Doris Day and Zero Mostel, both of whom were clients of Saul Jaffe (1914-1977), who was married to Kaplan’s daughter Selma (1915-2018). Frank Sinatra and Grace Kelly were also among his clients.

Congratulations to R.D. Eno, of Cabot, Vermont, who gets the prize. Extremely honorable mention to Uri Wilensky, of Glenview, Illinois, who got the answer but was just a little slower in responding.

Round 8

On December 8, 1950, a modern Orthodox rabbi in Pittsburgh named Morris Landes wrote to Rabbi Kaplan to introduce the work that would become Rabbi Landes’ doctoral dissertation at the University of Pittsburgh, an “analysis of the varying conceptions of the mitzvot massiot held by accepted leaders of American Jewish thought in the Reform, Reconstructionist, Conservative, and Orthodox ranks.” Rabbi Landes asked Rabbi Kaplan “to list ten men in the general Conservative ranks and ten among the Reconstructionists, who would be considered accepted leaders of their denominational thought. It is understood that the same names may appear in both lists. There is no desire here to put you in the difficult position of choosing the ten leaders of your denomination, merely ten representative leaders of denominational thought, whose published works are available, with the understanding that there might be others who might equally appear on this list.”

In a letter dated December 21, 1950, Rabbi Ira Eisenstein replied to Rabbi Landes on behalf of Rabbi Kaplan. Rabbi Eisenstein wrote that Rabbi Landes’ letter “was discussed by [Rabbi Kaplan] and one or two of us in the Reconstructionist Foundation office, and I am pleased to submit herewith the names of ten Reconstructionists whom you might want to use for your study. I think that it would be best for you to approach the Rabbinical Assembly of America to get the list of ten Conservative men.” (Rabbi Eisenstein for some reason did not mention in his letter that he was then the president of the Rabbinical Assembly.)

The list of Reconstructionist leaders set out in Rabbi Eisenstein’s letter included Rabbis Kaplan and Eisenstein themselves as well as Rabbis Eugene Kohn, Jack J. Cohen, and Milton Steinberg, who had died a few months earlier. The other five names on the list are far from obvious.

Question: What is the name of one of those other five people on the Reconstructionist list (two of whom were not rabbis)?

Answer: Rabbi Solomon Goldman, Rabbi Samuel Blumenfield, Dr. Samuel Dinin, Rabbi David Polish, and Dr. Jacob S. Golub (in the order listed in Rabbi Eisenstein’s letter). You can learn a little about each of these men by clicking on his name.

This round was really hard. The prize goes (again) to Professor (and Rabbi) Alan Brill. (If you are not familiar with Professor Brill’s wonderful blog, The Book of Doctrines and Opinions, you should check it out here: https://kavvanah.wordpress.com.) Professor Brill correctly identified Rabbi Goldman and Dr. Dinin. No one else got even one of the five.

Round 7

Question: What well-known rabbi claimed, in 1974, that he had persuaded Kaplan to add the word “religious” to his original definition of Judaism as “the evolving civilization of the Jewish people”? (Hint: That rabbi at the same time reported that he had turned down Kaplan’s invitation to serve on the first editorial board of The Reconstructionist magazine forty years earlier.)

Answer: Robert Gordis.

The prize goes to Rabbi Dennis Sasso, who set a new speed record by responding correctly within five minutes of our sending the question. Extremely honorable mention to Miriam Eisenstein, Benjamin Goldberg, Rabbi Richard Libowitz (the previous speed-record holder), and Marc Swetlitz, all of whom answered correctly, just a little less quickly.

Round 6

In a June 1972 letter, the writer said of the recipient that “you, and you only [were] the founder” of the Reconstructionist movement.

Question: Who wrote the letter, and to whom?

(a) Louis Finkelstein to Mordecai Kaplan

(b) Mordecai Kaplan to Ira Eisenstein

(c) Ira Eisenstein to Mordecai Kaplan

(d) Mordecai Kaplan to Harold Schulweis

(e) None of the above

Answer: (b) Mordecai Kaplan to Ira Eisenstein

The prize goes (again) to Rabbi Zachary Silver, whose expertise on Kaplan is evident elsewhere on this website. Extremely honorable mention to Abraham Clott, Ron Glickman, David Goldfarb, Rabbi Richard Hirsh, Eric Levine, Alan Marcum, Rabbi Arnold Rachlis, Rabbi Dennis Sasso, Carol Stern, and Rabbi Deborah Waxman, all of whom answered correctly, just less quickly.

Round 5

Question: What well-known rabbi wrote the following in his synagogue bulletin dated December 16, 1949?

“I am closest in spirit to Reconstructionism. My disagreements with it are minor. My approach to the Halachah and my conception of a modern Prayer Book may be somewhat to the right or left of it as you please. … The Prayer Book should be much briefer, less apologetic, argumentative, and sermonic than the Reconstructionists have made it. The Jews of to-day may perhaps still form the habit of praying if we give him [sic] little, and direct that little to his emotions. In other words, a service in our day must become, within our modern setting, what it was at its inception—drama, pageantry, song. It would make me happier if … the Reconstructionists realized that for those of us who take a modern view of revelation the theological discussion of the selection [sic] of Israel has become superfluous and monotonous; and … if they were less vague about their community approach. But there is blessing in what the Reconstructionists have thus far done, and of all of our present Jewish ideologies they hold out the greatest promise.”

Answer: Rabbi Solomon Goldman

The prize goes to Professor (and Rabbi) Alan Brill, of Seton Hall University.

The bulletin was that of Anshe Emet Synagogue in Chicago, the congregation that Rabbi Goldman served from 1929 until his death in 1953. Goldman was a devoted student of Kaplan’s, and, in addition to being one of the great pulpit rabbis of the 20th century, Goldman was one of the most important leaders of the American Zionist movement.

Round 4

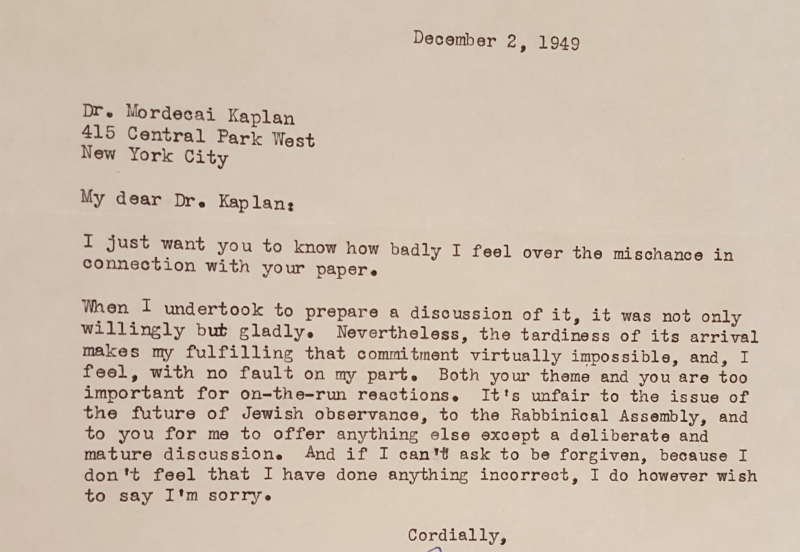

On December 6, 1949, in a speech to a conference of the Rabbinical Assembly of America, Mordecai Kaplan proposed the formal recognition of “Rightist, Centrist and Leftist groups” within the Conservative movement, and in particular the Committee on Jewish Law and Standards. [The speech was reprinted in Mordecai Waxman ed., Tradition and Change: The Development of Conservative Judaism (New York: The Burning Bush Press, 1958), pp. 289-312.] Kaplan believed that a sympathetic discussion of his proposal at the conference led by a particular prominent figure in the Conservative movement would have made its acceptance more likely, and Kaplan was very disappointed when that person declined to lead that discussion. On December 2, 1949, that person sent Kaplan the following letter:

[Courtesy of The Eisenstein Reconstructionist Archives of the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College.]

Question: Who wrote this letter?

Answer: Rabbi Milton Steinberg

Rabbi Steinberg, who died, tragically, at the age of 46 just a few months after having written this letter, was one of Kaplan’s most brilliant disciples and one of the great pulpit rabbis of the mid-20th century.

The prize goes to Rabbi Zachary Silver, whose expertise on Kaplan is evident elsewhere on this website. Popular answers to this question were Rabbi Louis Finkelstein and Rabbi Robert Gordis, both of which are good guesses.

Kaplan stated, more than once, that he believed that Louis Finkelstein, then the Chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America, was prepared to support Kaplan’s 1949 proposal until convinced not to do so by another member of the JTS faculty. Kaplan speculated that the objecting faculty member was Saul Lieberman (see Round 2 of the Kaplan Quiz, below).

Round 3

Question: Who wrote the following (in 1974)?

“If I had known about philosophy and theology what I have come to know since I became a professor of philosophies of religion, I would have refused to continue teaching under that title. Philosophy, as I now know it, is the immaculate conception of thought not sired by experience. Moreover, in view of Philo’s and Maimonides’ ‘negative theology,’ a theologian is a philosopher who admits he does not know what he is talking about and is proud of it.”

Answer: Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan

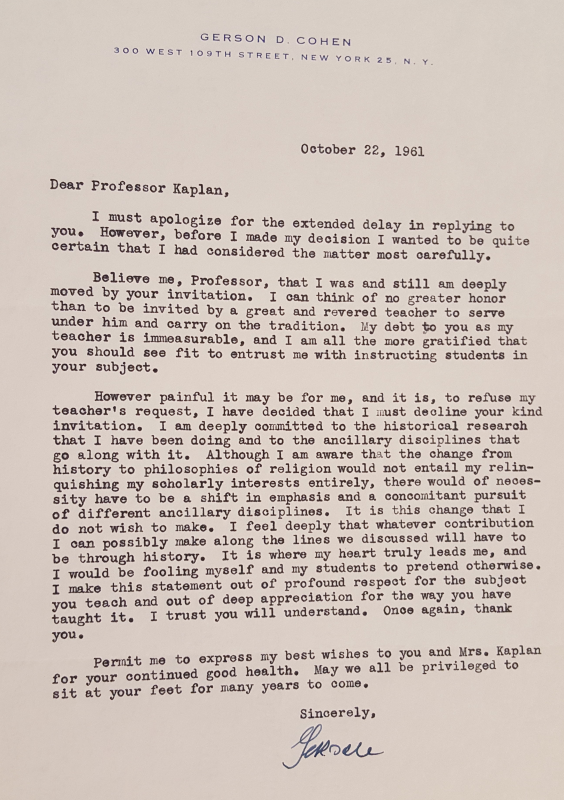

The text comes from a letter, dated May 10, 1974, that Kaplan wrote to his former student Gerson Cohen, then the Chancellor of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. Kaplan noted at the top of the letter that he did not mail it, without specifying a reason.

Although his position as a professor of homiletics at JTS is better known, Kaplan was indeed also a professor of philosophies of religion there. In the letter, Kaplan writes, “You [Cohen], no doubt, recall my having proposed to you that you succeed me when I retired as professor of philosophies of religion.”

[Addendum: We recently came upon the letter from Cohen to Kaplan, dated October 22, 1961, in which Cohen declined Kaplan’s invitation:

Courtesy of The Eisenstein Reconstructionist Archives of the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College.]

The prize goes (again) to Alan Septimus, who threatens to become the Ken Jennings of the Kaplan Quiz. The most frequently submitted answer to this question was Rabbi Dr. Neil Gillman, Kaplan’s student and devoted disciple (and, we are proud to say, Kaplan Center Senior Fellow), who indeed taught philosophy for many years at JTS.

We are surprised that no one raised the question of whether the writer had conflated (perhaps intentionally?) the doctrine of the immaculate conception with that of the virgin birth, but we will not opine on matters of non-Jewish ideology.

Round 2

Although deservedly famous as an important and influential Jewish thinker, Mordecai Kaplan is rarely given sufficient credit as a Jewish scholar, particularly in the field of Midrash. However, at least one very prominent Jewish scholar had great respect for Kaplan’s expertise in Midrash, as evinced by the following letter to Kaplan from 1941:

[Courtesy of The Eisenstein Reconstructionist Archives of the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College.]

Question: Who wrote this letter?

Answer: Saul Lieberman, perhaps the 20th century’s greatest Rabbinic texts scholar.

This was a very hard question. (Perhaps we should not have removed the Jewish Theological Seminary letterhead from the letter image, but we thought that would have been too broad a hint.)

Not surprisingly, only one of you, Professor (and Rabbi) Richard Libowitz, of Temple University, got the correct answer, and he is a Kaplan scholar who had previously read the letter! Among the good, educated guesses were Robert Gordis, Max Kadushin, Louis Ginzberg, J.D. Eisenstein, and Samuel Lachs.

Many have thought that Lieberman’s relationship to Kaplan could be captured in a single word: nemesis. That turns out to be an over-simplification. Lieberman clearly respected and valued Kaplan’s expertise on esoteric Midrash questions. Moreover, although Lieberman has been reported to have “honored” in some ways the Kaplan cherem (“excommunication”) in 1945, we have found a letter from Lieberman to Kaplan written (in Hebrew) less than three years later that is, at least to all appearances, extremely respectful. (One scholar, however, has suggested that at least some of the language in that letter may have been sarcastic.) Interestingly, according to Kaplan’s diary, when in 1959 Lieberman turned up as a guest at a small engagement party for Kaplan and Rivkah Brandstater Rieger, Kaplan was surprised, but apparently pleased, to learn that Lieberman was a cousin of Rivkah’s, and so shortly thereafter Lieberman became Kaplan’s relative by marriage. For more on the cherem, please click here.

Round 1

Question: Who wrote the following passage (published in 1967)?

“Religion is the sum total of the customs and teachings articulated and formulated by the religiosity of a certain epoch in a people’s life; its prescriptions and dogmas are rigidly determined and handed down as unalterably binding to all future generations, without regard for their newly developed religiosity, which seeks new forms. Religion is true so long as it is creative; but it is creative only so long as religiosity, accepting the yoke of the laws and doctrines, is able (often without even noticing it) to imbue them with new and incandescent meaning, so that they will seem to have been revealed to every generation anew, revealed today, thus answering man’s very own needs, needs alien to their fathers. But once religious rites and dogmas have become so rigid that religiosity cannot move them or no longer wants to comply with them, religion becomes uncreative and therefore untrue.”

(Thanks to Rabbi Shai Held for pointing us to this text.)

Answer: Martin Buber

The author was an important 20th century Jewish thinker whose first name begins with an “M” … but not Mordecai Kaplan, as, not surprisingly, quite a number of you thought.

Four of you got it. We had a tie for first place (chronologically, that is) — congratulations to Joshua Krug and to Alan Septimus. Honorable mention to Michael Blackman and Sam Fleischacker.

This was a tough question, I think, in part because, although the “religion”/”religiosity” distinction is classic Buber, the language of “accepting the yoke of the laws and doctrines” is not. Also, the stated publication date (1967), two years after Buber’s death, understandably may have thrown some people off track, for which I may owe you an apology. The text comes from a lecture, originally given in German more than 50 years earlier, titled (in English) “Jewish Religiosity,” which was published in 1967 in On Judaism, Nahum Glatzer’s collection of Buber’s addresses. (I do not think that the English version was published before 1967; please correct us if we are wrong.)

Mel Scult says that he has files titled, respectively, “Heschel as Kaplan” and “Kaplan as Heschel”. Perhaps this text will be the beginning of a “Buber as Kaplan” file. We know that Kaplan and Buber interacted in Palestine/Israel, but we know frustratingly little about the substance of those interactions. One small gem: In a letter from Kaplan to Rabbi Ira Eisenstein dated November 5, 1937, while Kaplan was a visiting professor at The Hebrew University in Jerusalem, he writes that “Buber has been hard at work learning Hebrew prefaratory to his coming to the University. He already knows enough to make himself understood. But he hasn’t acquired yet the knowledge of that Hebrew which he has to use in order not to be understood.”

In addition to Kaplan, Abraham Joshua Heschel was a popular answer to our quiz question, and a logical one because of the substantial influence of Buber’s thought on Heschel’s. (And my mention of Rabbi Shai Held was read by at least one of you as a clue to Heschel.)