In order to view or download the PowerPoint presentation for this program, please click here.

-

Recording of “Mordecai Kaplan at The Jewish Center” (5-24-20)

-

The Future of the American Jew: Mordecai Kaplan’s Vision Reappraised

Not yet on our e-mail list? We would love to add you. Please e-mail Dan Cedarbaum, at dan@kaplancenter.org.

In order to view or download the source sheets for this program (some of which we will discuss in detail), please click here.

[pdf-embedder url=”https://kaplancenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Kaplan-Center-flier-320-1.pdf” title=”Kaplan Center flier 320-1″] -

Learning Materials for Adults

From Dr. Jeffrey Schein

90th Anniversary Celebration of Judaism As a Civilization

Dr. Deborah Waxman and Elias Sacks on “Judaism as a Civilization: the 90th Anniversary of this Hanukkah Gift that Keeps Giving”.

We’d like to help our Institutional Friends utilize this both as a webinar in their own community and as useful public relations about the place of Kaplan in their own community.

In regard to the use in your own community of the celebration of the 90th anniversary of Judaism as a Civilization, I am suggesting a very simple format. In person or via Zoom (or both), view the webinar and have a delightful dialogue.

Here are a few sample questions that might guide the dialogue:

1. Think of the famous Francis Bacon quote that only a few books are of a nature that they should be chewed and slowly digested.

Why might Judaism as a Civilization be one of these?

2. Have there been books you have read that affected you the way Dr. Waxman describes Phillip Klutznick responding to Judaism as a Civilization?

3. Kaplan was personally rather modest but overflowing with enthusiasm about ideas. One of the greatest compliments he could pay you was if something you said or wrote was “Copernican” (i.e. turned the world upside down). What in your

mind is “Copernican” about redefining Judaism as a civilization rather than a religion.

4. Suppose a visitor from Mars landed in your own synagogue. The visitor assumed that what he is experiencing about Judaism is the way things always were. How would you help the visitor understand that the version of Judaism he is experiencing was a revolution?

The communal template we will be creating builds on the partnership between the Kaplan Center and the adult learning institute Hineini here in the Twin Cities. This institute is directed by Rabbi Debra Rappaport, an RRC grad. Together we are building a community program called “The Hidden Kaplanian Footsteps in the Twin Cities Community”. The program would combine viewing the recording of our December 10 webinar with the testimonies of local rabbis and community leaders about Kaplan’s influence on the architecture of Jewish life in the arenas of synagogue life, education, and the arts in our community. We think you can put together a similar program in your community that would give Kaplan his due and even more significantly enhance the status of your own synagogue in your community.

Mordecai Kaplan Through the Eyes of Ira Eisenstein

We recently made available digitally Ira Eisenstein’s books Creative Judaism and What We Mean by Religion, where we approached Kaplan through the lenses of Ira Eisenstein’s “primers” on Kaplan’s most important books (Judaism as a Civilization and The Meaning of God in Modern Jewish Religion).

Here is the link to the full set of communications and recordings used by Rabbi Lee Friedlander and Harriet Feiner for this course.

-

About Mordecai Kaplan

Mordecai Menahem Kaplan (June 11, 1881 – November 8, 1983) American rabbi and founder of Reconstructionism was born in Sventzian, Lithuania, the son of Rabbi Israel Kaplan and Chaya Nehama Kaplan. His father was a prominent Talmudic scholar who had received rabbinic ordination in Lithuania from the most outstanding rabbis of the day. The family emigrated to New York City when Mordecai was eight years old. Kaplan attended City College of New York (B.A. 1900), as well as Columbia University (M. A. 1905) and received rabbinical ordination from the Jewish Theological Seminary (1902).

The traditional education which he received mostly from his father, gave Kaplan a solid grounding in classical rabbinic texts. Because he had both a traditional and a secular education, spoke English without an accent, and thereby was able to relate to young people well, he was engaged as a minister [the title of rabbi came later] by the “modern” New York Orthodox congregation Kehilath Jeshurun in 1903.

Although the congregation was happy with his work, the young rabbi was tortured with doubts as his graduate studies began to undermine his traditional beliefs. During his last year at Kehilath Jeshurun (1908) he met and married Lena Rubin, daughter of a well-known family in the congregation. When in 1909 he was invited by Solomon Schechter, the head of the Jewish Theological Seminary, to become principal of its newly created Teachers’ Institute, Kaplan enthusiastically accepted the position. On his honeymoon to Europe he also met with Rabbi Isaac Jacob Reines from whom he received rabbinic ordination.

Kaplan remained at the Jewish Theological Seminary, the center of the Conservative movement, training rabbis and teachers until he retired in 1963. As the first director of the Teachers’ Institute, he laid the foundations for Jewish education in America. Working closely with Samson Benderly, the Director of the Board of Jewish Education in New York City, he helped train all of the educational leaders of the next generation.

Kaplan was a strong personality and a demanding teacher. For many years he taught homiletics and midrash (classical rabbinic homilies) to rabbinical students at the Seminary in addition to “Philosophies of Judaism.” Critical of his colleagues who seemed to be only concerned with scholarly issues, Kaplan dealt with the central religious questions that troubled his students. His own graduate studies where he had concentrated on sociology led him to formulate a religious ideology that emphasized the link between religion and experience. Because experience changes, religion changes, and thus Kaplan believed it important to find ways in which beliefs and rituals could function in the modern era as they did in the past. To do this might mean changing a ritual, dropping it completely, or substituting something new. Heavily influenced by the utilitarians and by William James, Kaplan called himself a functionalist. He was ready to pursue the path most likely to make religion and particularly Judaism functional in the American setting.

Although the perfection of the individual might be the aim of religion, Kaplan believed that this goal could only be achieved within the context of a community. He held that Jews must have more in common than their religion for Judaism to survive in the secular culture of the modern era. Throughout the ages Judaism as the evolving religious civilization of the Jewish people bound them together into a vital organic entity. A vigorous Jewish life in America could be brought into being he maintained only with the creation of new institutions appropriate to a democratic technologically advanced society. Kaplan had the vision of the expanded synagogue as the vehicle for the survival of Jewish Civilization. In 1917, the Jewish Center on 86th Street in Manhattan, a magnificent building with many recreational facilities in addition to a synagogue, was dedicated with Kaplan serving as rabbi. It quickly became the prototype for many other synagogues-centers in the United States and Canada.

Kaplan’s thinking became increasingly radical leading to his departure from the Jewish Center in 1922 with a large group of supporters to organize the Society for the Advancement of Judaism (SAJ), also in New York City. He attempted to establish his ideology, which he called Reconstructionism, as a school of thought within the Jewish community rather than as a separate denomination in order not to contribute to the fragmentation of American Jewry. Reconstructionism defined Judaism as an evolving religious civilization and stressed Judaism’s quest for social justice as well as individual salvation or fulfillment as the primary values of Jewish life.

In 1934 Kaplan published his magnum opus, Judaism as a Civilization, which became the landmark for second generation American Jewish leaders desperately seeking a way to live both as Jews and as Americans. He held that one could live in two civilizations (the Jewish and the American) without any sense of tension or contradiction because the two cultures were absolutely compatible. His major thrust was to set the Jewish people, their past experience and their present welfare at the center of his conception of Judaism. The Torah (Hebrew Scriptures) revelation and God were all explained in terms relating to Jewish peoplehood. Because he did not see Judaism as a system of dogmas or a set of laws, he helped even the most skeptical of modern Jews to relate to Jewish civilization.

In the years following the publication of his magnum opus in 1934, Kaplan produced a series of works that spelled out his philosophy. Of particular importance are The Meaning of God in Modern Jewish Religion (1937), his primary theological work, and The Future of the American Jew (1948) where he concentrated on the application of his philosophy.

Kaplan used his position as rabbi at the SAJ to explore new rituals, reformulate liturgies and experiment with new prayers. In 1922, he inaugurated the first Bat Mitzvah when his daughter Judith turned 12½. The New Haggadah (for the Passover seder service) which he published in 1941 and The Sabbath Prayerbook which appeared in 1945 shocked and outraged many traditional Jews. In 1945 following the publication of his prayerbook, he was excommunicated (a herem or ban was issued) by the Union of Orthodox Rabbis of the United States and Canada and according to the New York Times, his prayerbook was publicly burned during the herem ceremony held at the Hotel McAlpin in New York City.

Kaplan was a lifelong Zionist believing that Jewish civilization required the natural setting of its own land in order to flourish and grow. Active in Zionist affairs, he represented the Zionist Organization of America at the opening exercises of the Hebrew University in 1925. He was a good friend of Chaim Weizmann who visited him whenever the Zionist leader was in New York. Deeply influenced by the cultural Zionist Ahad Ha-Am, Kaplan later stated that this Zionist thinker revealed to him “the spiritual reality of the Jewish people.”

Kaplan’s Zionism and his devotion to the Jewish people existed alongside a very profound commitment to American culture and its ideals. Not only were the values of American Jewish Civilization mutually supportive but Jewish culture (or any subculture) must be the vehicle for transmitting democratic values. His metaphor for American ethnic life was not the melting-pot where differences disappeared but, like his colleague Horace Kallen, the orchestra where the various voices blended together in perfect harmony. In addition, Kaplan believed that the Jewish community in America must be pluralistic i.e. hospitable to all forms of Jewish commitment and that there must be a place for democracy even within the synagogue where Jews choose under the guidance of their rabbi the ways to express their values and beliefs. According to Kaplan, when it comes to Jewish life in a modern democratic society, tradition and the Jewish law have a “vote but not a veto” over group policies and individual behavior.

-

Tikun Ha’Ir (Repairing the City): An Immersive Project in Hunger and Homelessness

Primary Contact: Pam Sommers

pam.sommers@adatshalom.net

Adat Shalom Reconstructionist CongregationThough it’s impossible to thoroughly simulate what it’s like to worry about where your next meal is coming from, or where you will sleep at night, the Tikkun Ha’Ir Immersive Project in Hunger and Homelessness seeks to have its participants experience, as well as examine and discuss these issues.

For three days and two nights, middle/high school students live in a church parish hall and work primarily in a Washington DC neighborhood undergoing rapid gentrification. While engaging in simulations of life in a shelter and food insecurity, they spend much of their time preparing and serving meals at an area food kitchen, and delivering fresh produce from a local farmers market to residents of three apartment buildings providing affordable living to seniors and those with disabilities. They also spend time assisting at a neighborhood family shelter and learning what eviction entails. At all of these venues they meet with managers and directors who educate them about each organization and carve out time for questions. Participants travel on foot or via metro to all of these places, accompanied by adult team leaders.

At the start of the program, participants are divided into teams of 5. Each team is given the amount of cash equivalent to a family living on federal SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) benefits. Each team decides how that money will pay for all of the food they will consume for the duration of the Project. They may purchase food from the local supermarket, fast food places, or purchase items from an in-house “store” set up by team leaders. In addition, each team participates in an “Iron Chef”-like competition, preparing a meal judged on presentation, creativity, taste, nutritional value and cost (the lowest gets the most points).

Each evening, participants gather for study, discussion and “Roses and Thorns” observations. The Torah is our primary source, with additional readings by both ancient and contemporary scholars (e.g., Don Isaac Abarbanel, Matthew Desmond, Rabbi Jill Jacobs). Everyone is expected to eventually bring all that they’ve studied/experienced back to our Adat Shalom community. They will contribute to a collective bimah presentation on hunger and homelessness as part of the chanting of Isaiah’s haftarah during the Yom Kippur Morning service. In addition, they will serve as ambassadors to the younger members of the community and their families, inspiring tikkun olam projects in class and at home.

Like so many places of worship, Adat Shalom is working hard to keep the post-B-Mitzvah cohort engaged. It’s abundantly clear that work and worship can take place in a mishkan of one’s own making, so why not let teens create a temporary spiritual home of their own devising? Have them interacting with the “gair” (stranger) that is mentioned so frequently in the Torah, but in immediate, hands-on, resonant situations? And then bring back that experience to their familiar spiritual home?

And I certainly look at this Project as a template, something that can be refashioned in a variety of ways to suit myriad populations and locations.

The inspiration for this project comes from two main sources. Certainly the words of Isaiah. And most significantly, from a community of Haitian people with whom I have had the privilege to work, break bread, celebrate and worship . After the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, Rabbi Sid Schwarz, Adat Shalom’s founding rabbi, traveled to that ravaged country and, upon his return, encouraged me to organize a service mission to Leogane, the epicenter of the quake. That experience–which has resulted in four subsequent missions, and a close relationship with Pastor John Felix and his amazing NICL school, congregation and community – opened my mind about poverty, faith, hands-on education and learning from/working alongside those you have come to “help”.

-

Aaron and the Wrath of God

Aaron and the Wrath of God gives teachers an opportunity to explore the parallels between guiding children as a parent and guiding them as a teacher. It is also is an exploration of three different (highly interrelated yet distinct) goals for our teaching about God. The story can stand on its own as a Rudyard Kipling like “just so story.” It also can be an occasion for digging more deeply into our own assumptions about good teaching about God as suggested in the analysis that follows the story.

Aaron and the Wrath of God by Tuvya Ben Shlomo (Philadelphia Jewish Exponent, July 31, 1984)

Analysis of Aaron and the Wrath of God by Dr. Jeffrey Schein

Questions to Explore the High Holiday Themes in this Story

- The father is working very hard to understand what Aaron really means? Why is that so hard? When do we not seem to understand even the people we love?

- In your own words, what is bothering Aaron about God?

- Do you agree with Aaron that God is too big and strong to be doing so much punishing?

- If you could argue with God what would you argue about?

- Could God have convinced Aaron that he was right to have judged the Israelites so harshly?

- Can you think of a time when your actions were judged through justice? Mercy?

- Why is is hard to know when to judge with mercy and justice?

- Would it be okay if god never punished?

- Any suggestions for God about when she moves between the two chairs? iit

-

An Evolving Vision: Add Your Voices

Our 21st Century Kaplanian Vision of Jewish Education is very much a work – in – process.

We fully hope and expect that it will continue to evolve as different people engage with these materials in different ways, in different contexts, for different reasons. We welcome all of it.

After all, how better to honor Kaplan’s legacy than by allowing his ideas to inspire vigorous and robust dialogue and debate about Jewish education in the 21st Century?

Please ADD YOUR VOICE now.

- Let us know how you use and experience these materials!

- Offer comments, questions and reflections at the bottom of any page

- Email divrei Torah, lesson plans, or text study notes that draw upon these resources

-

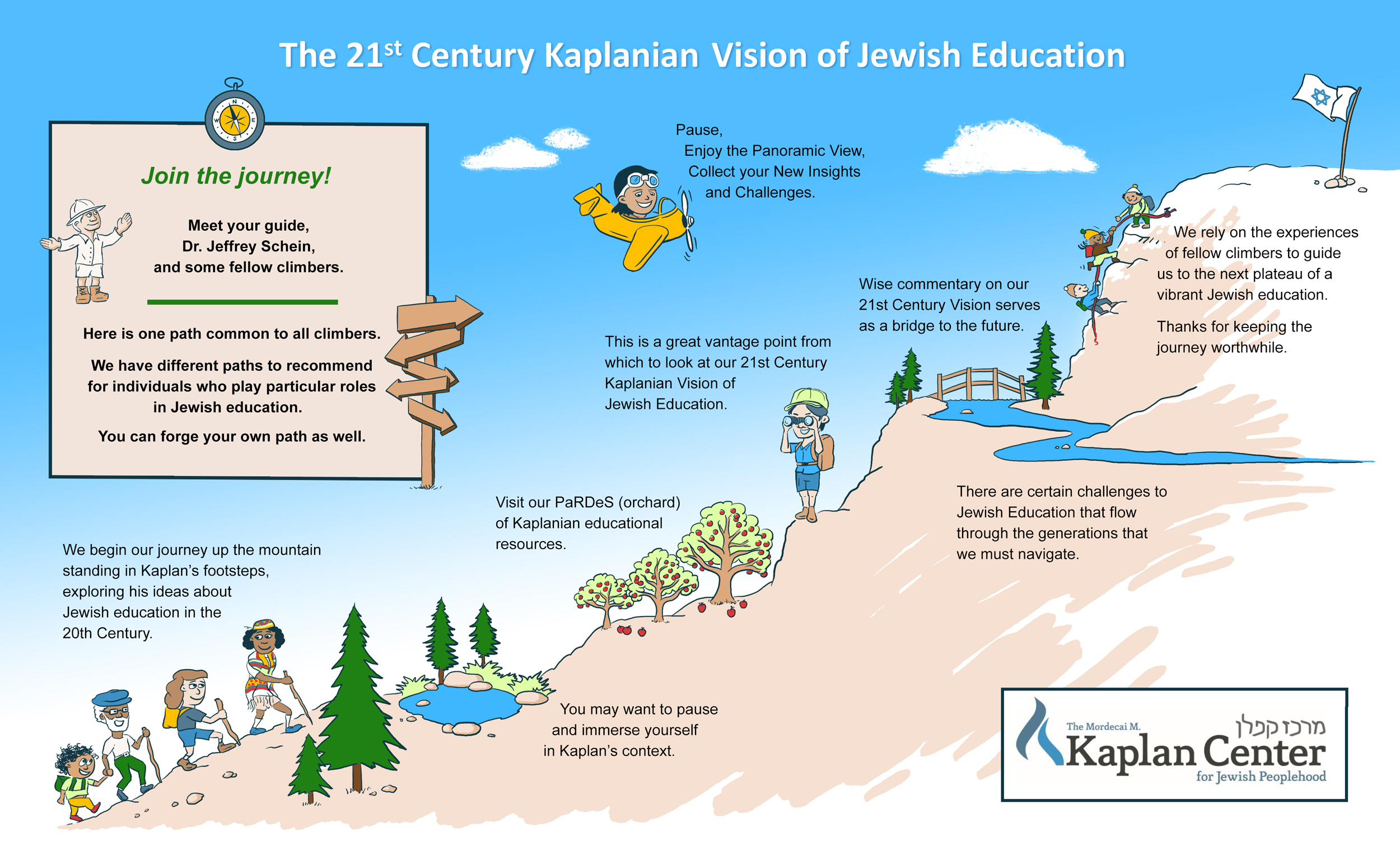

21st Century Kaplanian Educational Vision

(This is an interactive graphic. Tap or click on different objects in the picture to go to the corresponding project webpage.)

Shalom! Welcome to our 21st Century Kaplanian Vision of Jewish Education!

Whatever city, country, continent, or planet you have journeyed from, we are glad that you have landed on the home page of the 21st Century Kaplanian Vision of Jewish Education.

We hope the resources you find here will both nurture and challenge your own and your community’s thinking about contemporary Jewish education.

As you will see below, our assumptions are non-linear; there are many places to begin.

Wherever you begin, our prayer is that you will emerge from your exploration of this project enriched and inspired.

Enjoy any or all of these entry points:

- Revisit Kaplan’s 20th Century Vision of Jewish Education with texts drawn directly from Judaism as a Civilization

- Utilize the Kaplanian Educational Resources in our PaRDeS / Orchard

- Contemplate Our 21st Century Kaplanian Vision of Jewish Education

- Explore an Array of Insightful Responses to our 21st Century Kaplanian Vision

- Contemplate our 21st Century Vision in the context of Enduring Jewish Educational Challenges

- Help our 21st Century Kaplanian Vision CONTINUE TO EVOLVE:

- Let us know how you use and experience these materials!

- Offer comments, questions and reflections at the bottom of any page

- Email divrei Torah, lesson plans, or text study notes that draw upon these resources

-

Jewish Artist of the Week

Primary Contact: Dvir Cahana

theameninstitute@gmail.com

jewishcreativity.orgCreativity is a Jewish value. Viewing ancient ideas through new perspectives is a crucial aspect of the Jewish experience. As Jews, when we enter the millennia-long discourse on the Jewish tradition, we gain a sense of ownership over our identities.

Historically, however, the people who have been given the power to make meaning from Jewish texts have been a small, privileged group. This is especially unfortunate because we stand to gain so much when bringing more voices into the conversation. What we aim to do is to empower a broader group of creative souls to investigate texts and interpret them. We want to give these individuals permission to enter the creative conversation and trailblaze new ways of reading our scriptures.

We offer a wide variety of programming geared toward several different audiences. For working artists, we have the J.A.W. and Ore’ach Fellowship, a paired-study fellowship between practitioners and rabbis over two months. The fellowship results in presentations of work inspired by this paired study experience. For the general art-making public, we offer a growing network of weekly art nights, retreats, and other programming.

We are not just a group of artists. We are a community. That’s why we started the Amen Network, an affiliation of many different partner institutions that work with us to share the art we make as widely as possible. We also underwrite Amen Productions, our in-house musical and artistic content hub.

Art, for us, is a bridge. It connects career artists with their Jewish heritage, and it connects the broader Jewish community to its Judaism as well. Making art shouldn’t be intimidating; it should be healing. It is our mission to harness the connective, healing properties of art-making as we continue to build on the Amen Institute’s mission.

________________________________________________________

-

Judaism and Democracy Webinar

Entering the Heichal (sanctuary) of the Voting Booth: Reflections on Judaism and Democracy

with Rabbi Elliot Dorff, Sarah Hurwitz, Rabbi Sid Schwarz, Lauren Grabelle Herrmann

October 30, 2022

Question: What do you get when you bring together….

One of the foremost Jewish philosopher thinkers on our contemporary scene (Rabbi Elliot Dorff)

A practitioner-philosopher of a Jewish future that demands an amplified voice for Tikkun Olam (Rabbi Sid Schwarz)

…and a distinguished author and former speechwriter for Barack Obama (Sarah Hurwitz)?

Plus a d’var by SAJ’s Rabbi Lauren Grabelle Herrmann!

Answer:A dialogue about Judaism and Democracy you will not want to miss!

Elliot Dorff, Rabbi, Ph.D., is Rector and Distinguished Service Professor of

Philosophy at American Jewish University and Visiting Professor at UCLA School of Law. He has chaired the Conservative Movement’s Committee on Jewish Law and Standards for fifteen years and has served on three federal government commissions — on health care, on diminishing the spread of sexually transmitted diseases, and on the protocols for research on human subjects. His books relevant to today’s session are these: To Do the Right and the Good: A Jewish Approach to Modern Social Ethics, and For the Love of God and People: A Philosophy of Jewish Law, especially Chapter One in both books.

Rabbi Sid Schwarz is a social entrepreneur, author and teacher. He is currently a Senior Fellow at Hazon, a national organization based in New York.

Rabbi Sid founded and led PANIM: The Institute for Jewish Leadership and Values for 21 years; its work centered on integrating Jewish learning, Jewish values and social responsibility. He is also the founding rabbi of Adat Shalom Reconstructionist Congregation in Bethesda, MD where he continues to teach and lead services. Dr. Schwarz holds a Ph.D. in Jewish history and is the author of two groundbreaking books–Finding a Spiritual Home: How a New Generation of Jews Can Transform the American Synagogue (Jewish Lights, 2000) and Judaism and Justice: The Jewish Passion to Repair the World (Jewish Lights, 2006).

Rabbi Sid directs the Clergy Leadership Incubator (CLI), a program that trains rabbis to be visionary spiritual leaders. He also created and directs the Kenissa: Communities of Meaning Network which is identifying, convening and building the capacity of emerging spiritual communities across the country.

Sid was awarded the prestigious Covenant Award for his pioneering work in the field of Jewish education and was named by Newsweek as one of the 50 most influential rabbis in North America. Sid’s most recent book is Jewish Megatrends: Charting the Course of the American Jewish Future (Jewish Lights, 2013).

From 2009 to 2017, Sarah Hurwitz served as a White House speechwriter, first as a senior speechwriter for President Barack Obama and then as head speechwriter for First Lady Michelle Obama. Prior to serving in the Obama Administration, Sarah was chief speechwriter for Hillary Clinton on her 2008 presidential campaign. Sarah is a graduate of Harvard College and Harvard Law school, and she is the author of Here All Along: Finding Meaning, Spirituality, and a Deeper Connection to Life – in Judaism (After Finally Choosing to Look There).

Lauren Grabelle Herrmann serves as the rabbi to SAJ (Society for the Advancement of Judaism), the first Reconstructionist synagogue in the United States, founded by Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan. SAJ is a congregation dedicated to joyous spirituality, intellectual exploration, community, and social justice. Before coming to the SAJ, Rabbi Lauren was the founding rabbi of Kol Tzedek, a dynamic and diverse spiritual community in West Philadelphia. She founded the congregation during her student years at The Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, which she graduated from in 2006. Among Rabbi Lauren’s passions are ritual and social justice. She has been a leader in interfaith work in Philadelphia and is involved with T’ruah and interfaith organizing in NYC. She is the co-chair of the rabbinic council of Jews for Racial and Economic Justice (JFREJ).

Many thanks to the sponsors of this webinar: Jacobs-Cedarbaum Family, Joe Kanfer – Director of the Lippman Kanfer Foundation for Living Torah, Sam Kelman Family Foundation, Josh and Debra Levin, Sherwood and Barbara Malamud, Karol and Daniel Musher, and Rabbi Arnie Rachlis